Year Two

In June of 2023, my mom and I flew from my home in NYC to Dubai, and then to Islamabad. We met with my grandfather and spent a day in Islamabad, and the next morning, we flew 45 minutes to Skardu. The flight to Skardu is mesmerizing because you are literally flying through the mountains. Pilots even need to be specifically trained to fly this route. Any signs of bad weather result in this flight's cancellation.

Unlike last summer (2022), instead of remaining in Basha Valley, this summer we explored many different areas of Baltistan, including Skardu, Bashu, Muchlo, Khaplu, and Doghni. I brought 207 DfG pads and 333 pinkie pads with me. My goal was to distribute these pads to the Iqra Fund school girls.

Even though there is a language barrier, periods are universal and a phenomenon that all cis-girls experience. Therefore I believe distributing resources for them to use is imperative, as it will keep them in school and make their life easier. No girl should be disadvantaged, or have her education interrupted, because of menstruation.

The Journey

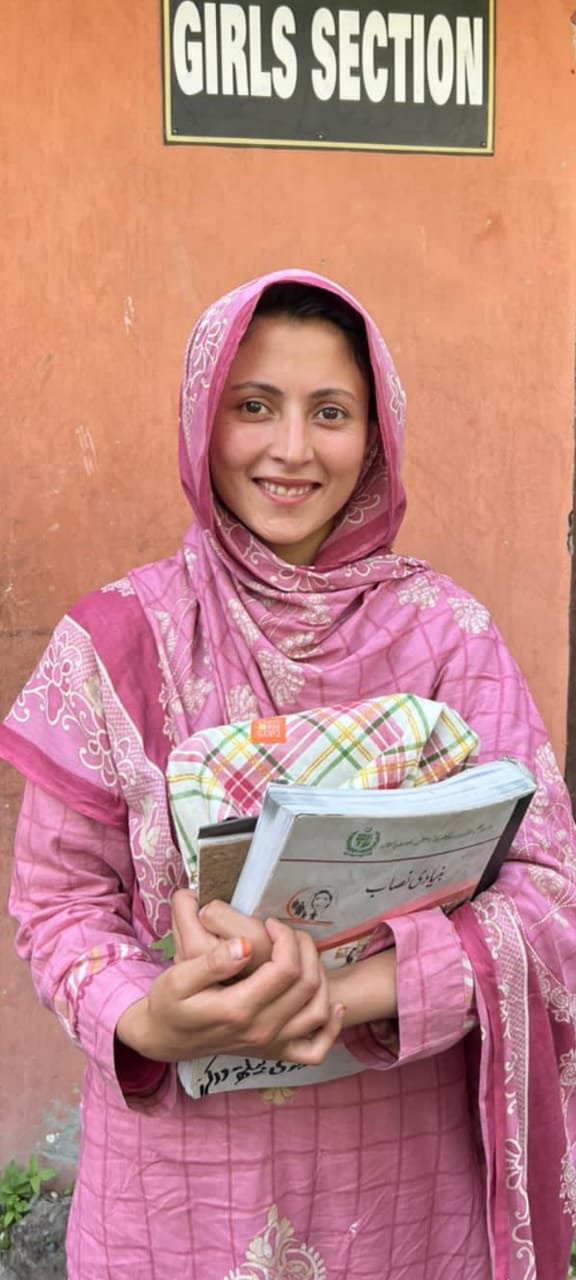

On day one, after arriving in Skardu from Islamabad, my mother, grandfather and I drove directly from the airport to the Iqra Fund office. We had a meeting with many of the Iqra Fund team members, where we discussed the goal of this trip and created an itinerary. Afterwards, we visited a nearby hostel with Genevieve, the founder of Iqra Fund, and two female members, Naureen and Naila.

The hostel houses scholarship students from different regions of Baltistan who have come to Skardu to advance their studies. The hostel leader, Ghulam Muhammad, warmly greeted us and the girls gave us flower necklaces and hats. Afterwards, Genevieve, my mother, and I sat in a room with 22 female high school students between the ages of 13 - 18.

After a brief introduction, and once Ghulam Muhammad left the room, I introduced the kits. Because Sakina Batool, the lady health worker who is government funded, was present, it was appropriate for me to distribute them. I would not have been allowed to without her presence. When NGOs and people who are not government funded come, they are not welcomed by the villages. The locals don’t like people interfering. The NGOs and nonprofits need acceptance from the village elders and MSG (Mothers Support Group), and for a lady healthcare worker, like Sakina, to be present.

Day One

They also said they use cotton rags during their period and even share them. We highlighted that menstrual products should never be shared, including the DfG pads, as it leads to infections.The girls are also embarrassed to dry the rags outside because they are white and often are stained, so they wear them wet. But the DfG liners are colored and patterned and look just like cloth, and therefore can be hung outside without the embarrassment. Some of the girls even said during menstruation they do not bathe at all. We told them to not intentionally avoid bathing while menstruating and to use the soap and a washcloth in the DfG kit to cleanse themselves. They even asked questions like if they could use soap to clean their private parts and we clarified them. I noticed that the community in this region is very hospitable because no matter where we went, we would be offered food and tea.

During Ramadan, when you are on your period you are not supposed to fast. However, the girls said they pretend to, in public. The girls said periods are not considered impure anymore, but they are not celebrated either, or ever really mentioned. Only one girl out of 20 said that her mother had informed her about menstruation. The rest learned from her friends or older sisters.

After introducing the kits, we asked the girls to tell us a little about themselves; their names, how long they have been in this hostel, their villages, and their dreams. The girls wanted to be army doctors, healthcare workers, lawyers, and teachers. Sakina told the group how they could have babies from age 18 to 49. It wasn’t clear to me whether she was advising them that they could biologically only have children between those ages, or whether they should aim to only have children between those ages.

I explained how the kits worked and gave a visual demonstration by holding one up. I also showed them how to insert two liners, to accommodate a heavy flow. At first the students were shy and giggling, but they quickly opened up and were very excited to receive the kits.

Sakina also pitched in and told us about her studies and how she wants to continue to pursue medicine. She told us that she has started distributing birth control pills and has injection form of them too, which have been provided by the government. I was pleasantly surprised about this. I was also very pleased when the girls began asking me personal questions such as how to manage period pain and cramps. One girl even said she went to the doctor because of painful period cramps and he dismissed her, and said that once she was married her pain problem would automatically be solved.

I was supposed to hand out a survey that I constructed with Project Baala, but instead I just asked the questions on the survey in a group setting, because I thought that would be more effective and keep everyone more comfortable. I asked them about their periods and focused on missed school days and how much of the biology they knew about menstruation. Half of the girls raised their hands when I asked if they missed school because of their period.

On Day Two, we drove three hours from Shigar (our hotel’s location) to Bashu Valley. The first hour was on a flat, paved road, but after that, we ascended up the valley through the mountains on an extremely narrow (two cars cannot pass), winding, and rocky dirt road. The journey was extremely uncomfortable and scary at some points. This immediately made me realize how difficult it would be to get products up into the mountains and why people in those villages almost never leave.

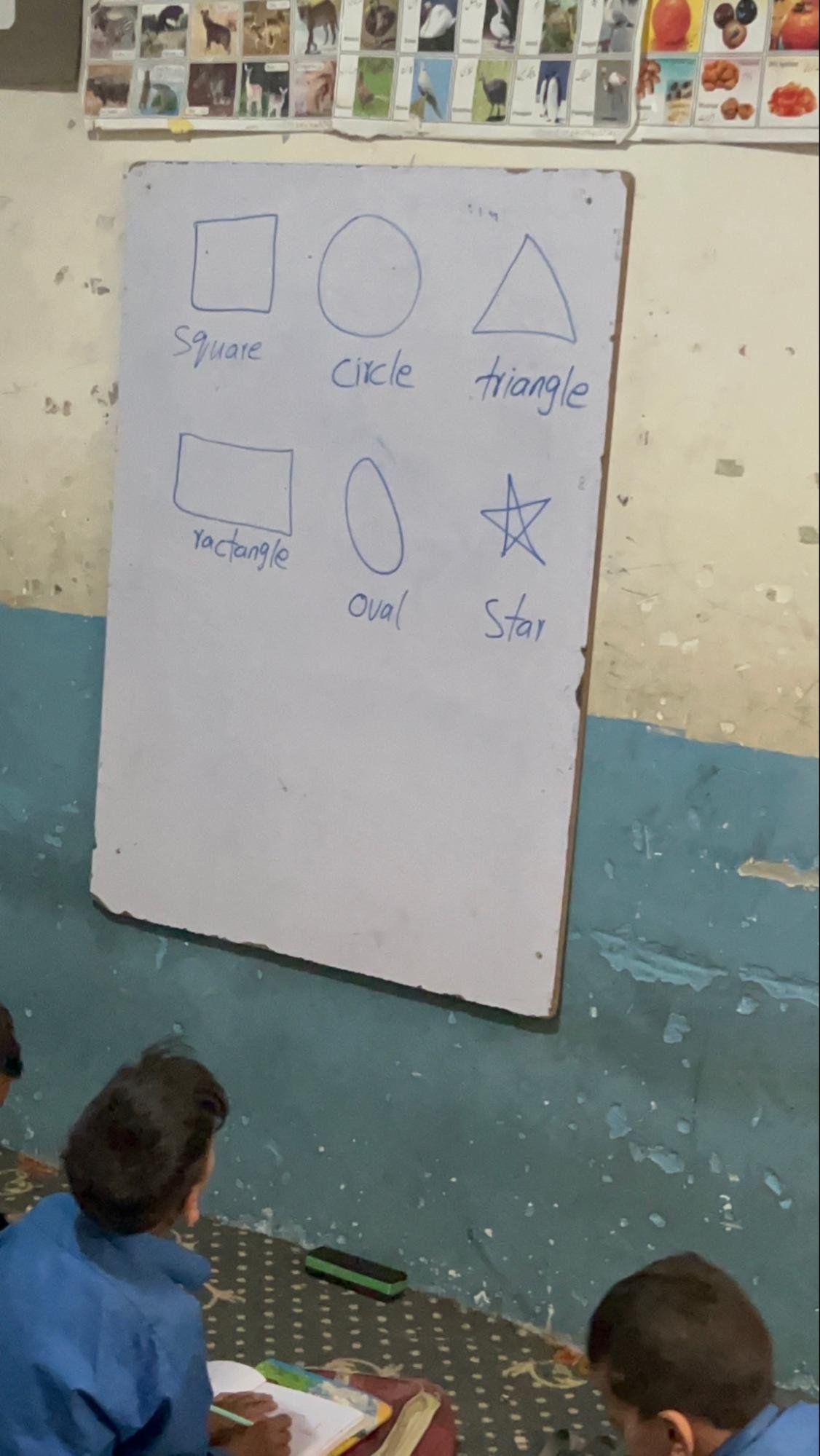

When we arrived at the school, we were welcomed very warmly. The students threw rose petals on us, and a group of young boys were holding up welcome signs. The students were very excited by our arrival, especially because we were with the founder of Iqra. After introductions, we viewed a co-ed 8th grade classroom with 20+ students. The teacher told us that 100% of the 8th grade students passed their exams, and 100% of the girls will continue into 9th grade. Afterwards, we went to an ECD (early childhood development) classroom, Iqra Fund’s new development. It was heartwarming seeing these young students sing songs to us that contained important basic knowledge (days of the week, body parts, numbers), in English, Urdu, and their local dialect. This program is very promising as it begins educating these kids at an even earlier age. Then we watched the school assembly, which began with prayers. The principal invited some of the Iqra Fund members and supporters, including my mother and grandfather to give quick speeches.

Day Two

After leaving the classroom, there was a cluster of village residents outside of the school, announcing their concerns to Genevieve and other Iqra Fund members. A mother who was carrying her small child was asking if they could provide a scholarship for her daughter who had not made the cut. She only spoke Balti, so my mother and I could not understand her at all. But because Genevieve was familiar with her daughter and she was high on the scholarship list, Genevieve promised to fulfill her desire. It was inspiring to see this mother advocate for her daughter's education, even if it meant her daughter would have to move away from home. But if the mother had not approached Genevieve, her daughter would most likely not have been given this opportunity. At the very end, the teachers expressed their gratitude to Iqra Fund as they were empowering a new generation of educated girls.

We could not distribute pads because we did not have a lady healthcare worker with us. Without one, the community can get upset, as it seems like we were pushing an agenda on them.

The Iqra Fund members were discussing with the teachers and parents, but I was sitting down because I was dehydrated. A few of the girls from the 9th grade classroom approached me and invited me to their classroom. I was surprised that they approached me, but of course, was also thrilled. When I first entered their classroom, we were all laughing because of the language barrier. I was able to introduce myself in Urdu ,and say my name and where I live, but I do not speak enough Urdu to hold a conversation. Instead, I asked simple questions like their name, grade, and dreams. I quickly noticed that these girls' English was limited compared to the scholarship students. However, they could say their dream jobs in English, and many of them wanted to be doctors, pilots, lawyers, and teachers: this pattern was common among all the students. They then asked what classes I took, my dream job, and if I majored in art or science. I could understand their questions, but could not respond, and therefore I brought my mom into the classroom to translate.

The students said that men inherit everything, but that women have started speaking up about gaining rights concerning possessions, and having their own possessions

On Day Three, we met with scholarship students as well as Iqra Fund’s female workers, Naila, Naureen, Aimen, and founder, Genevieve, in their office in Skardu. I gave out kits to the scholarship workers and the Iqra Fund workers. Naila said I should prioritize the distribution of kits, even while I am not physically there.

We then asked the students how we could help them. One of the students told us that besides feminine hygiene, they wanted basic first aid training. They wanted to learn how to treat cuts, dehydration, and injuries. They also asked if it was appropriate for Iqra Fund to provide that, as well as nutritional awareness.

The students in the hostel only get meat twice a week, but still get enough food, and more than they would get at home. This is not the case for many as most children in the region often lack sustenance.

Day Three

After asking the girls about their dream professions, one said psychiatry because her grandfather was mentally ill and no one had the knowledge to help him. Others wanted to be doctors in order to provide for their communities. The students are “agents of change.” They are also extremely grateful for these scholarships because without them they would probably be getting married in their villages. The students also told us that men currently inherit everything – women are not usually included in family wills. But they also said that women have started speaking up about gaining rights concerning possessions, and having their own possessions.

The students are outspoken and want to help students in their village by asking Iqra Fund to provide transportation, tutors, and more scholarships. If students do not have a scholarship, and their parents do not make enough money, they can not continue their education, even if they want to. Lastly, the girls wanted a six month English course after school, because if they are going to study in Islamabad, Karachi, or Lahore they need to improve their English.

Amina Hanif, an experienced climber, also joined us later. She has climbed 7,000 meter peaks all over the world including in her home, Baltistan, as well as Iran and Spain. She also talked about how important the pads were for women.

On Day Four, we drove two hours from Shigar to Khaplu. On the way, we stopped at Doghni, a small village, to meet one of my grandfather's old friends. After arriving, we visited Karima Gulshan, a lady healthcare worker, who has a small facility in a female-owned building. Her facility has a variety of medicines, and she even has a rented ultrasound machine, which she brings with her when she visits other villages.

Karima charges very little, to make her practice accessible for everyone. She ends up barely breaking even at the end of each month because of this. I gave her 30 DfG pads with five disposable pinkie pads added to each kit. She will distribute these kits to school girls when she goes to Khaplu and Muchlu. Karima thought the DfG kits were amazing as they would keep the girls in school and limit infections, which many girls come to her with. She also told us that a few years ago, someone she knew got her period on a bus, and, not having any supplies with her, had to use a cloth she found on the side of the road. Unfortunately, she got an infection, and later died from it. Karima is focused on promoting basic awareness about health. She also wants more materials for her practice, which Pads for Pakistan wants to help with.

Day Four

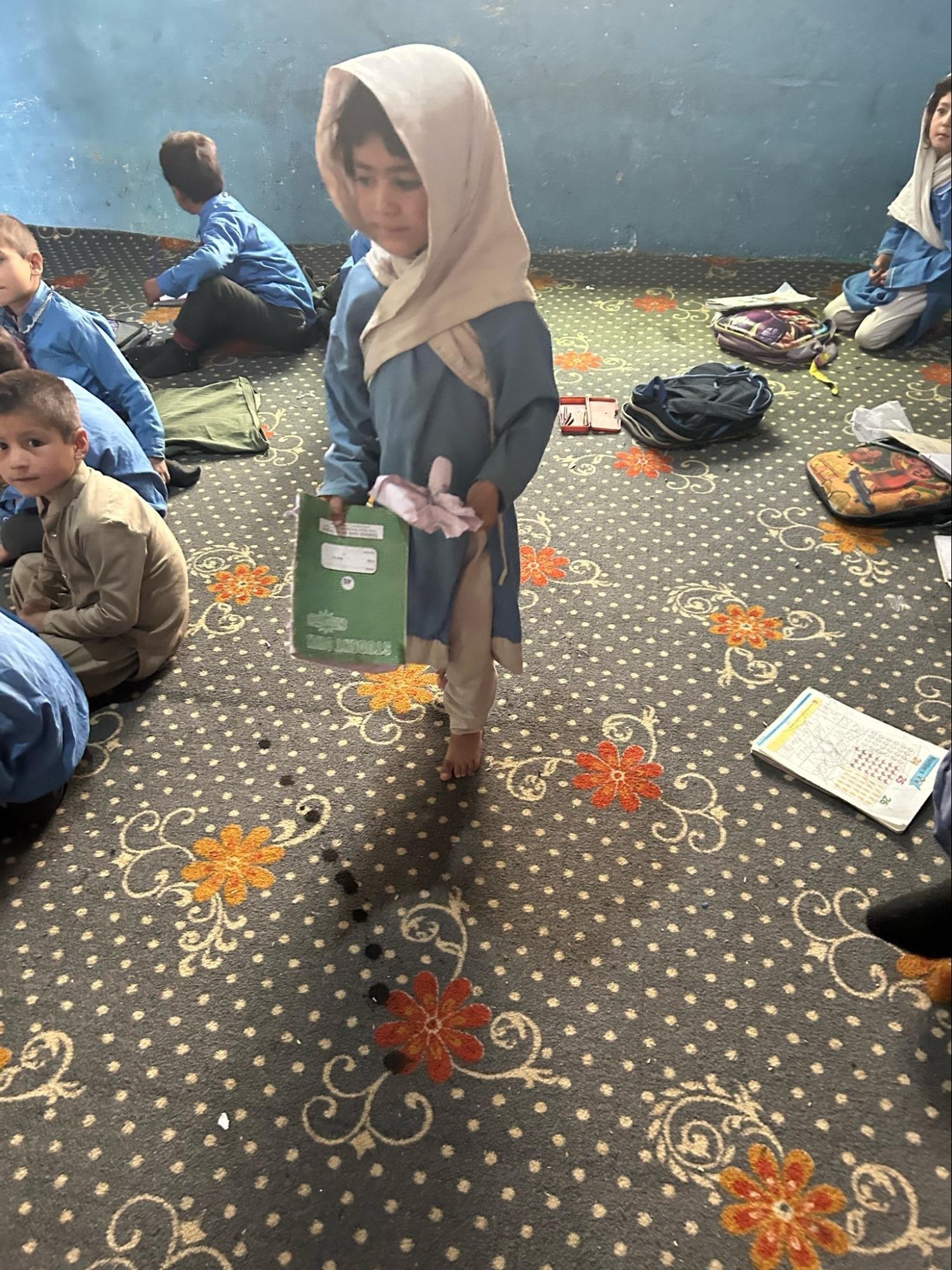

On Day Five, we drove an hour from Khaplu to Muchlo to visit the schools in this region. The first school we visited was Pre-K to 5th grade. These schools were established by the Felix Foundation, a Spanish non-profit organization, but Iqra Fund recently took them over and supplied new teachers. However, this first school was still understaffed. There was one female teacher supervising two classrooms of younger children. The community pays her a salary of 5000 rupees per month (around $16), so she cannot really support herself.

These younger kids were extremely confident and loud, and overall energetic. We went into a few of the classrooms to peak into their studies. When we asked about their favorite subjects, there were a variety of answers, from math and science to English, history, and Urdu. The classroom decorations also stood out to me, as the walls contained lots of important fundamentals, like letters and numbers, days and months, in colorful displays.

After visiting the classrooms, we discussed with the principal and teachers before going to Iqra Fund board member Saima Machlovi’s family house. There we met two elderly men, Rustom and Shamshir, who are community leaders in Muchlo. They had traveled the world, and had been the ones who went to Spain and convinced the Felix Foundation to provide teachers for the two schools here. They have been big advocates for education for all for over 30 years.

Day Five

I think Muchlu was more progressive than the other villages I visited. But even still, when given the opportunity, students will still go to cities to receive the best education.

We then drove to the other Iqra Fund school in Muchlo. The students and teachers also greeted us very kindly and in an elaborate way. The second school was very modern. Surprisingly, it even had a computer room, and served all grades. The building was the nicest facility I have seen in this region. We only had time to do a quick tour, but again could not give out pads because we did not have a lady healthcare worker with us, and were surrounded by men. Lastly, we went to a climbing school across the street where we continued to talk to teachers, and Rustom and Shamshir.

This trip definitely opened my eyes to the extent of period taboo still present in Pakistani communities, as well as the lack of basic knowledge. The fact that most girls’ mothers do not educate them about menstruation shocked me. The prolific sharing and reusing of dirty cloths, and resulting infections, also surprised and saddened me.

I was also surprised, pleasantly, at the ambitions of many of the girls – for example medicine, psychiatry, law, and more. They all wanted to be in professions that would allow them to give back to their communities, and all intended to return, even if they went away to big cities to study.

I plan to follow up with the female healthcare workers in a month or so, to ask about the success of the pads we distributed, and whether the girls are using them correctly. This will help me to plan what we should bring and what it might be useful for us to teach next year. Next year, I also intend to bring more general health supplies, including basic first aid supplies, for people like Karima. Next year I also intend to try to organize the attendance of lady healthcare workers at each location before we go, as this prevented us from distributing pads in some locations this year.